Rick becomes a Conquistadore

- Justin Holle

- Dec 30, 2023

- 23 min read

2023 La Ruta de los Conquistadores Recap

Abandoning the age-related story appears to be the best move going forward. Sure, Rick has nearly 7 decades under his belt but hanging that over this La Ruta de los Conquistadores story gives you, the reader, a chance to retort back with your own age-defying quip. You’ll surely share a story you once heard about a campesino on the Nicoya peninsula who still rides his horse every day, at the ripe age of 96. Then I’ll fire back that my Great-Grandma still had spunk as she nearly reached 102.

We’ll fight about who’s story carries the most weight and we’ll walk away unsatisfied. So let’s pivot our focus. 3 years ago Rick found himself surfing in Jaco, Costa Rica and off-handedly mentioned his desire to pick up mountain biking to his surf instructor Leo. Without missing a beat Leo mentioned that Costa Rica has a mountain bike race each year. It’s been going on for nearly 30 years and follows the route the Spanish took in the 1650’s. The route changes slightly each year but always lasts 3 days. The 3 day format came after local television wouldn’t give Roman, the founder, the opportunity to run it longer as it’d steal TV time from soccer. Racing coast-to-coast forces riders through the heart of the Carara National Park, the only transition forest in Central Pacific which results in an explosion of flora and fauna in a convergence of dry and humid forests. Riders pedal up and over the two highest volcanos in Costa Rica, Turrialba and Irazú. Oh, they are both active volcanos and Irazú’s potential for natural disaster would dramatically change the entire Central Valley. The 3rd challenge? Just your standard hot, humid, high-octane, full-gas race rip through banana plantations.

La Ruta is a race for seasoned mountain bikers. Leo’s suggestion that Rick take aim at La Ruta, as he bobbed naively in the calm Pacific surf, with no mountain bike experience, may have been in haste. But the fuse was lit.

That first year resulted in a broken collarbone. An injury sure to set an athlete on the sideline for a bit of time. However after a morning surgery, Rick picked up an indoor trainer at REI and assembled it, with his single operational arm, and set to an indoor spin. He’s not taken a day off from fitness for over 4 years. This athlete, who I’d yet to meet, applies his grit and tenacity to every endeavor: road racing in his 20’s, rock climbing, fatherhood, and building his successful CPA firm. “Mountain biking is just another way for me to continue to grow,” he’s reminded me many times. So while that first year put him in a sling on a trainer he bumbled along learning as most of us do with bruises and scrapes with gashed shins and scratched frames. But much like his locating of Leo, an accomplished surer/businessman/leader in Costa Rica, he knew he could fast-track his learning with some help.

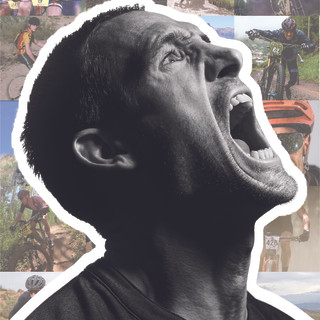

This La Ruta story isn’t about a 68 year-old finishing one of the hardest races in the world. This story is about two men working together as coach and athlete. This is a 2-year journey culminating with a 3-day ride across a country. Our embrace at the finish line on Day 3, in the final minutes of light, capped off a nearly miraculous victory by a newbie mountain biker. A novice who’d only raced a few small events but had the confidence to line up with world-class athletes in Central America.

Rick and I’s 2024 La Ruta Race Stats:

Day 1 :: 3 hrs 33 min 02 sec

43 miles 893’ elev gain

Day 2 :: 8 hrs 16 min 08 sec

42 miles 10,200’ elev gain

Day 3 :: 12 hrs 18 min 21 sec

70 miles 11,000’ elev gain

9th Place Men’s 60+ // 185th & 186th of 187 finishers // 40+ DNFs

Developing a training program for short-track, XC style racing requires a lot of “top-end” or threshold efforts. The training program for longer races, 100K to 100 mile efforts, requires some top-end work connected with longer, endurance pace bridges. Toss in some quality Zone 2 work to help raise the athlete’s floor (lowest acceptable effort level) and you’ll find success at the end of a 5 to 12 hour event. But Stage Racing? This beast of a format needs the kitchen sink. Athletes must be able to twist the gas on a hard effort when needed, maintain a high endurance level for hours, and then twist the throttle some more. But the real challenge? They must be able to repeat this for a second, third, and sometimes several days in a row. Training for this type of challenge should follow the path outlined above. An athlete should build up to the stage format after growing through shorter, single-day events. Did I mention Rick isn’t a normal athlete?

Our training relationship started off with excitement, like-mindedness, and curiosity with a side dish of skepticism. The first Dawn to Dusk (DtD) Training Camp brought Rick to Tucson, AZ for 3 days of fitness and riding in mid-February of 2022. He committed to that first camp with the disclaimer that he’d probably just do one of the camps as he has a busy work and life schedule. 3 day camps require 5 days away and his calendar probably didn’t allow for it. After helping him rebuild his bike in his room at the El Conquistadore Resort he handed me a check for the year’s training agreement and we shook hands, committing ourselves to a 200% relationship, each bringing our entire selves to the project.

15 hours later Rick was careening off trail into a pile of rocks. The Oro Valley, AZ desert consuming a chunk of his flesh. From that first fall onward Rick donated genetic material to the 50 Year Trail, the Tucson Mountain Park, and Honeybee Canyon. But… He never once hesitated to remount his Revel mountain bike. He never tossed his hands in defeat. He never quit being the athlete that’d taken him atop Denali in his climbing days. He kept trying. He kept forward motion.

With skin tattered and bruises setting to purple Rick and I reconvened before he left Tucson. He committed to the next camp. I’d see him in March in St. George, Utah.

At 8AM we were swinging kettlebells, jumping boxes, and pulling on TRX bands. By 11 we were dissecting the psyche behind reaching further. Answering questions like, “In the last 12 months, what’s been your biggest struggle in your: body? heart? mind?”. By 1pm we were pedaling. In Tucson I learned that Rick was tough, physically. In St. George I learned Rick was invincible. Rick reminds me of those sand-weighted, inflatable boxing toys I had as a kid. I recall one specific toy that featured WWF’s Ultimate Warrior. I’d punch, kick, tackle, and abuse that thing and in just a few short seconds it’d upright itself for another round.

One of the longer training rides forced me to double back with Rick and suggest we amend the prescribed route. “Let’s take this trail for a couple miles and bolt left, back to Inn Santa Clara,” I suggested. “I’m good. I want to do the whole route,” he replied. And here’s the moment a coach must take a breath. On one hand I am responsible for the safety of athlete’s following my guidance and training protocol. On the other hand I want each athlete to know they alone control the success of their program. They choose what to eat, when to sleep, if they pedal, and how they adhere to my suggestions. They drive the vehicle and only with that level of ownership can an athlete dig into their highest potential. So I relented. Rick had the route, the bike, food, hydration, and a phone. “Call me if you get into trouble Rick!”

I didn’t get a phone call.

The sun set.

A familiar routine would emerge. Rick would disappear. I’d worry. I’d even try to retrace steps, backtrack on trails, turn on geolocating to his devices, and every so often let a dark thought creep in. Each time I’d find my worry pointless. Rick can’t be killed. The rebounding boxing bag of MTB athletes.

Knocking on my door at Inn Santa Clara broke me from the worried thoughts. Rick’s smiling face stood proud on my doorstep. He’d completed the full route much the same way he’d make his way back on course in Bentonville in April, and up and over Searle Pass en route to Copper Mountain from Leadville in July. Just when worry would build to the feeling of negligence, Rick would appear. Sometimes battered, sometimes depleted, but always safe and most importantly, smiling. We started 2022 with his reluctance to negotiate a complicated schedule. We began riding with flat pedals and a tentative commitment to “clip in”. The year ended with his complete compliance to a 365-day-a-year training program and the hunger to push forward. Our first good fortune struck when the 2022 edition of La Ruta ran in May, too early for Rick to be prepared. We’d set sights on 2023.

Year 2. DtD hosted camps in Tucson, Las Vegas, Bentonville, Crested Butte, and Sedona. Rick came back to Arizona and took back his pound of flesh. Clipped in, upright, and far more skilled than the previous year, Rick pushed he and bike around the challenging desert. His development monumental. Our fitness trajectory still needed work but the skills were opening new doors. May would come quick and La Ruta still seemed a fantasy.

Our second bit of good fortune struck. The 2023 La Ruta de los Conquistadores would run at the end of November and beginning of December. This gave us almost an entire year to get the fitness, the skills, and the confidence on track for the 11/30 start line. When it rains it pours. The 2023 La Ruta would be run in reverse. The reverse-course meant we’d end with the soul-crushing, body-beating, muddy, humid, stifling heat of the Carara National Park. The stretch of jungle that swallowed Lance Armstrong in 2018, leaving him with his head hanging between his legs battling heat exhaustion. Instead of preparing for a 12-hour Day 1 wrestling match with jungle terrain we could ease our way into the 3 days. The light grew much brighter as we stared into our 2023 training tunnel.

I mentioned Rick was smart right? Surely you remember me pointing out he’s an accountant. So by default he’s smart, a real nerd. Good thing. Rick’s smarts knew he needed any help he could get. A new bike appeared at Red Rocks Cycling in Morrison, CO. New shoes, new training gear, a new helmet. All of the little pieces began forming our picture. Rick reached out to another specialist in helping mature athletes balance their training efforts with age-related muscle loss and changes to energy systems. His pursuit of The Hardest MTB Race in the World would know not a single limitation. Family trip to Paris? “Where do I find a bike,” he asked?

And a funny thing happened… his business kept growing. His family kept maturing. The pieces of Rick’s life that initially required our management of his training calendar grew alongside his abilities and fitness. Was it perfect? Surely not, how could it be? But did it work? Let’s find out.

“Smart then Steady then Survival. That’s our strategy for the race,” I told Rick as we buckled into our 5AM flight from Denver to Houston. “Sounds exactly like what I had thought,” Rick replied. We didn’t expand much past that in terms of race strategy. Having completed La Ruta three times (2018, 2019, and 2022) I knew that on paper the race looked monstrous. Further, having been in that jungle three times in 5 years I knew it was just unrelenting. It is an absolute juggernaut. Sure, the riding is hard. But the necessary eating, the early morning alarms, the constant action required outside the racing to prep gear, transportation, and self-care takes its toll on an athlete. I could talk Rick through every piece of knowledge I’d gleaned from my career behind a number plate, or, I could be there with him. I could ride the race along his side so that the needed tips, encouragement, and support wouldn’t be there just at aid stations or on start lines but in real-time, in the battle, when he needed it most. Would that take away from his goal of doing La Ruta? No, we agreed. It’d make it attainable.

Day 1, smart.

40-ish miles and less than 1,000’ feet of climbing sounds like a laughable “MTB race route” in Colorado where we rank our efforts in thousands of feet of climbing. How could the hardest mountain bike stage race in the world have such a mundane sounding first day? Answer: take those 40 miles and drop them on the east coast of Costa Rica. Dial it up to 90 degrees Fahrenheit and sprinkle it with 90+% humidity. Then bury the hundreds of competitors in banana fields and force them to pedal wheel-to-wheel above their Functional Threshold Power. That’s how.

Rick could’ve finished faster. If we were doing a 1-day race leaving and finishing in Siquirres, Costa Rica he would’ve. Instead we rode smart. The heat, humidity, and excitement meant he’d still be above threshold, heart-rate wise, but we aimed to avoid any muscle damage. Day 1, on this version of the route, gave us the chance to keep relatively fresh muscles for the day ahead. We did it. At one point a conga line of bananas popped out from the field to our left and Rick deftly dodged, then ducked, through the obstacle. As we neared the finish a strip of barbed wire attempted to peel my scalp but my Lazer helmet kept it at bay. So much of mountain biking is luck, pure and simple. On Day 1 we were smart and a wee bit lucky. We bested our 4 hour goal time by nearly 30 minutes and readied for Day 2.

Day 2, steady.

After my Day 2 finish in 2022 a familiar character on this blog, Brian Elander, mentioned how he’d “like to climb this hill. It looks soooo steeeeep and goooood!” At just past 7AM, December 1, 2023 I can confirm what I had assumed 19 months earlier, he is absolutely wrong.

The volcano stage rides like an escalator confused on its programmed direction. Each uphill punctuated by a quick flat or downhill reprieve that immediately fades from memory with the next steep grade. Rick and I hung in the back half of the peloton through town. Trading positions and words of encouragement with a group of riders from McCall, Idaho kept the mood light. Turning into the first coffee farm roads dialed up the effort. Our Steady Strategy meant we’d work to keep the pedals turning. Sounds easy right?

Cross a river with your bike and you realize streams are no big deal. Finish a ride with a broken crank arm, pedaling with a single leg for 5 miles, and you realize a squeaky cleat isn’t world ending. The lesson is perspective here folks. Endurance MTB events offer endless perspective lessons. Prior to Day 2 Rick mentioned that he’d be best off walking climbs that exceeded much past 10%. Just a minute into that first coffee finca we were pedaling 15%. Rick’s assumption blown. Rick’s perspective shifted. When he was still pedaling at 20% his entire reality redefined itself. The single coaching cue was for him to slow down his cadence and grind steady. Keeping a lower cadence helps keep a lower heart rate, keep good traction, and keep forward momentum. With childlike glee Rick kept hollering the current grade amazed at what he was doing. That youthful spirit and willingness to learn reminded me why Rick was built to be a conquistadore. …and I had a trick up my sleeve.

“I’m stopping for sunscreen, keep going!” I hollered to Rick as I pulled over at a small tienda. His body language never changed. Head forward, heels down, and pedaling purposefully Rick made a smooth right hand turn and disappeared up another steep road.

No protector solar. But… taking a page from my Baja Divide adventure lesson book, I grabbed something else, paid, and remounted my SuperCaliber. Chasing down Rick became my own race within the race. As directed, he’d steam right through aid stations where I’d stop and reload his 2, 3 or 4 bottles with Maurten drink mix (Rick’s preferred calorie drink. Me? I’m a CarboRocket man.) and I’d chase him back down to hand off a bottle or two and keep the others stashed for later use. We repeated this many times on Days 2 and 3, 8 and 12 bottles respectively. Before you think about my repeated efforts chasing down Rick, think about the determination needed to pedal through every single opportunity for a rest and a nibble. Per our strategy, Rick had no down time. No non-moving time. That’s a heroic commitment. I had the luxury of eating sandwiches, crunching through bags of plantain chips, and cheeking handfuls of trail mix while I mixed bottles and reloaded my Orange Mud 20L pack. Then the chase would begin and I get my interval efforts in.

So back to the failed sunscreen attempt. I chase Rick down. He’s partway up a never-ending climb to the top of Volcán Turrialba and I swing to his left with a treat. That giddy kid buried inside Rick? He came out again as I handed over a frozen, fruity popsicle. Under the blazing sun, on a paved climb well over his 10% limit, Rick savored a sugary cooling moment…without slowing down his pedals.

Sometime after we crossed over the top of that first volcano, through the aid station with just minutes to spare ahead of the cutoff, we began the second ascent of the day. Volcán Irazú. By the time we’d top out this final climb we will have ascended over 10,000’ of elevation in under 30 miles. For comparison that’s the same elevation gain over the entire course of the Leadville 100. I told you, this was a day without breaks. Rick knew this was a day without breaks. Steady.

Once we left that first coffee farm nobody passed us. Our strategy was paying off and we stayed on track with our position firmly held. How did we end up at the very end of the finish list? The others fell off. Cut from the race at one of many mandatory time limits. The Hardest MTB Race in the World must have cutoffs. I’d made this point clear to Rick many times and his “ride to the death” mentality wouldn’t be enough. We needed to outride his preset pace. We needed to push, steadily, all day. We needed to ride hard when riding hard is the last thing he wanted to do. No limits. That’s where we found ourselves as we cruised through farms and pastures high above the valley. Our good fortune striking again with perfectly clear skies. In years past I’d descended these same roads swallowed by low hanging clouds and fog. I’d nearly killed myself in a head-on collision with a tractor. Then a horse. Then a truck. These obstacles appearing in an instant and gone the next in my blind pursuit of the finish line. Now, looking upward I knew why those experiences thrilled me to the core. Steep roads make for cheese-grated brake pads and high speeds. In the opposite direction under the brilliant sun they make for stunning views. The rear view inspired a different thrill. The sweep vehicle crept up on our path and hung a few meters back. Are they going to pull us?

Time to chat with these fellas. 3 race officials alternated between hanging on the side of the road and bridging back up to us. On their 3rd or 4th bridge I rolled back and rode alongside their truck. Explaining our position and justifying our pace strategy did little to shake their path. They were under race directions to trail the final riders of the event. There you have it, we were in last but ahead of everyone who hadn’t made the cutoffs. So I challenged the sweep truck to a race up the next hill and punched an 800+ watt effort. There is still debate on who won but one thing was clear, they weren’t there to pull us from the course.

Steady continued to pay off. We passed a rider who’d been battling cramps and alternated between walking and pedaling. Then another. By the time we topped our second volcano for the day we’d moved away from the sweep truck and had the chance to put in a gap. Downhill.

Tucson 2022 Rick couldn’t downhill for s***. November 2023 Costa Rica Rick chased my wheel with complete confidence. Swooping in and out of steep pavement, loose gravel, and rutted farm roads like a seasoned MTBer. Another racer ahead became another racer left behind. Finishing the second day in a bit over 8 hours meant we’d crossed over. We could start Day 3. We could seek the coveted goal. Sure, an entire jungle stood between us and victory but that was a tomorrow problem. Today we relished a post-race meal. We slid our worn bodies onto massage tables overlooking rainforest and used our final bit of energy to simply close our eyes.

Day 3, survival.

Overly dramatic you say? 11,000 feet of climbing. 70 miles of racing. And a 3 mile jungle section that will take nearly 3 hours to cross. Who’s dramatic now?

To survive Day 3 will be the greatest effort of Rick’s mountain biking career, that cute little career he started just a couple years ago. What better way to kick it off than a 3:30AM alarm?

Racers trickled into the hotel restaurant dragging tired legs and looking a bit lost. The buffet could do that to a calorie-deprived athlete. “Where to start,” asked their eyes. “When to stop,” asked my stomach. Costa Rican breakfast. The apex meal. A year before I sat in this same lobby cajoling Harley into eating just a little bit more. We’d done the traditional route in 2022 and after his 12+ hour day in the jungle he’d been battling extreme fatigue and doubting his ability to begin Day 2. Fast-forward and Rick ambled over to the table with a plate of food knowing he’d need a good start to the day’s intake. Remembering the look in Harley’s eyes when I asked him to give the day a try brought back the reality of our final ride’s demand. Today was going to be long. Today was going to be hard. …better take another serving of rice and eggs. NOTE: Harley bounced back heroically and finished the event strong.

La Ruta’s finish line didn’t register as a goal. I wasn’t focused on the entirety of what we needed to do today so I didn’t want Rick thinking about it either. We had a sole mission: Make Aid Station 3, the jungle cutoff, by noon. That’s it. We make that cutoff and we have the opportunity to enter the Carara Jungle and attempt to cross. Miss that cutoff and we miss out on being 2023 Conquistadores.

Like a comfortable couple handing a napkin before the other asks or offering a blanket before the other shivers. Rick and I slide into our routine. Pedal, drink, a little push in the back, and repeat. We wound our way out of San Jose and already witnessed riders pulling out. One from an early crash. Another from an uncooperative stomach. The bikes atop the sweep van grew as the efforts compounded. Determined to stay on the bike I crisscrossed a road that broke over 30% grade and topped out as Rick hiked alongside several other racers. Using the extra time to pop into a store I returned to Rick with a creamsicle and a high five. “We got this amigo!” I hollered as he remounted and pedaled through the next aid station. Having committed to abandoning the age story (boy, it’d really add a piece of inspiration here…) I’ll stick with explaining what happens to the body after hours spent operating at maximum effort.

Our nervous system struggles to come back online. Responsible for determining where to send energy, when, and for how long takes a toll. The sympathetic system stays fully engaged as each threat is addressed, catalogued, and responded to appropriately. Hours of this exhaust our system and it takes more than calories and CBD to get it back in working order. This automatic system needs time to rest and recover. Stage racing lacks just that: time and recovery. The athlete then fights an uphill battle. Our system begs for a break and not only do we ignore the request we double down on a demand for effort. Muscles, minds, and spirits matter not in this equation. So how do you overcome it without the rest? We don’t. We simply cope. We understand that without a fully functioning nervous system we may feel weak but still be able to push our pedals. We may feel sluggish but be riding faster than we ever have. It’s a strange out-of-body experience and often this foreign feeling is in a foreign environment. So while we have depleted functioning we are having unique experiences demanding even more mental processing. Whoa. That does sound hard. We accept the struggle and we continue. Survival.

Aid Station 3. 10:45AM. Rick the Indefatigable shows up once again. On this occasion, and with the time buffer, he said he needed to stop and get some pebbles out of his shoes.

They weren’t pebbles.

Once blisters pop on the underside of the foot the blown skin can rub back and forth under a sock and feel like a pebble is trapped in the shoe. Nope. That is your body falling apart on you. Welcome to the jungle. Watch it bring you to your knees.

Rick spent less than 3 minutes addressing his failing flesh and pedaled away. I mixed bottles, stuffed a potato and refried bean taco in my mouth and took chase with a swelled feeling in my chest. The swelling soon took over and I needed to share my emotions with someone who’d understand! Before I rejoined Rick I called Abbe, she didn’t answer. I called Harley, he answered. At Base Camp Cyclery in Denver, CO Harley took my FaceTime call and instantly knew the magnitude of what we’d done. “We made the freaking jungle man! We are going to do this!!” I screamed. He matched my enthusiasm and spun the camera around to share the good news with several people at his Small Business Saturday event. From the jungle to the mountains we were spreading good cheer! Why didn’t I save this celebration for when I rejoined Rick? Because the job wasn’t done yet.

The hour and fifteen minute buffer we’d built getting to the jungle wasn’t a bonus. It’d prove to be absolutely critical in our upcoming miles.

Watching Howard the Duck a few months ago reminded me that memories are fiction. I loved that movie. Memories are purely made up. That movie sucks. I’ve been reminded this so many times. No matter how many times I’ve climbed the infamous Powerline at the LT100 it always hits harder in the final 20 miles of that amazing race in August. Hiking a 14er? Always more challenging than I remember. And riding a mountain bike through the Carara jungle? Maybe the hardest thing one can do with a bike. Harder yet is the fact that you can’t make it go any faster by riding harder. The terrain limits power. The chest-high ruts force a rider to the precariously perched position between the ruts. Speed increases as the route steepens before meeting a river crossing and the margin for error exponentially decreases. Scared yet? It’s rowdy and I didn’t want either Rick nor I to take a digger. Proceed expeditiously but with caution. For the first few up and downs…

Then the train comes completely off the tracks.

Riding transitions into hiking. Racing into surviving. Forward into “that way”. It was here, at the crux of the race, with Rick shoving his Revel bike up a 20+% muddy pitch where I saw what needed to be done. We began this journey together, unified in the single goal of taking the novice mountain biker to the end of the hardest MTB race in the world, in 2 years. Working together as a team. Time to drive it home. I pulled Rick’s bottle from his bike, told him to drink while he hiked, and left my bike alone sinking in the mud. His expression blanked. “I’ve got it,” he retorted. “Yes, I know Rick, but remember you’ve got to be able to ride another 20 miles after we leave this jungle. I’ll meet you at the top. Please drink that whole bottle.” And I took off with his bike cradled on my shoulder. Time to cross-train.

The other racers looked on incredulously. “What. Is. Happening,” their expressions asked. Teamwork and commitment fellas. Take a good look.

We worked in unison. Once the grade mellowed to suitable walking I’d drop his bike, hustle down the steep mudslide, grab my bike, and retrace the route uphill as Rick continued pushing and pedaling ahead. I’d chase. Catch. Descend. Repeat. That’s how we made the jungle stage and how we kept ourselves ahead of the dreaded cutoff. The heat tried to slow down our progress but we pressed on. Muscles attempted to speak up, angrily, and we calmed them. Together we couldn’t be deterred and a few hours later we emerged victorious from the hardest MTB route I’ve encountered. Rick understood what we just did. The magnitude of it not lost on him. He’d been fueling solely on Maurten and ketones for almost 3 days of racing so thought it only fair that he take a break and ask for cup of Coca-Cola. The aid station volunteers, Ticos, jumped into action. The nicest, most helpful people on the planet only deterred by my direction, “Rick, you gotta go man. You gotta go now.” I knew what was still ahead and he did what Rick does. Got on his bike and pedaled away while I started to fill bottles.

We’d made the aid station exit with only 10 minutes left before the cutoff.

Short hills are worse than long hills. Short hills have the band-aid tearing ability to instantly rip away good spirits. That’s the type of short hill that Rick met just after the aid station. That jubilant, jungle-winning moment immediately lost to the 30% grade straight ahead. He surely hiked it, but I never saw. “I’ll catch him before the next hill,” I told myself. Yet he wasn’t there. Nor at the third. “Uh-oh”. He did the Rick-thing. Both of our GPS units quit working in the jungle and thus the preloaded routes were unavailable. We were reliant on the marked, albeit well-marked, course to ensure our choice of turns, but Rick repeatedly proves that he can twist a route into a curly straw fit for a Vegas Strip drink. “Did he lose the course?” The thought couldn’t be ignored. Dread begged to be let in.

I increased my chase pace but for the first time in the event my legs bounced signals back. I was fatigued. I needed to reign it in and pursue steadily. I pulled out the electrolyte chewable tabs and took 4. I ate a gel packet. And then, just ahead, there he was. Relief. “You really kept it going steady,” I said calmly disguising the panic that nearly overtook me. He just smiled. Damn I love Rick.

The final aid station appeared on the edges of a small town. Earlier racers must’ve enjoyed the La Ruta standard: a station stocked not only with drinks and eats but animated, encouraging helpers. We didn’t need that. We hadn’t needed that much over the past few days. We were fortunate to need only water because I have a feeling we startled the few guys left at the final aid station. Rick rolled on by but I halted their breakdown routine for 4 bottles of water. We’d made the final aid station with less than 5 minutes left on the clock.

Every minute counted. The 3 minutes spent digging phantom rocks from his shoes. The 1 minute for a roadside pee. The 30 second chat as we transitioned from hiking to biking atop one of the numerous rutted hills. The denied Coca-Cola. Every minute meant everything. We’d passed the last cutoff and within the next 15 minutes we’d see trucks and SUVs roll by loaded with bikes we’d just been racing alongside. Competitors who weren’t so lucky. Racers who had just as much, or even more, ability to conquer this route but missed the final cutoff maybe by mere seconds. Others who looked at the final hills and relented, admitted defeat. Each of them full of guts, each of them infinitely stronger than those who will never attend this race. While I appreciate the effort each of them gave I let the smile slowly creep across my mud-stained face. We are so close.

As the sun began to fall more than set on the final hills ahead I knew we’d soon see the beacon drawing us to the race’s finish line. The ocean. The other ocean, opposite from our starting ocean. So cool… Rick heard me ask a question he assumed would never be uttered, “Can you stop a second,” I asked? Puzzled but compliant he pulled up behind me and stopped. “Turn around,” I suggested and Rick too saw the improbable sight. He knew we were about to close the book on this thing. What would that mean?

We were ready to find out.

For 3 days I’d been remembering this course in reverse. Being the inaugural edition run East-to-West offered a unique memory challenge game. I’m pretty good at overturning cards with lemons, soccer balls, and umbrellas. Matching them to clear a board never challenged me. Remembering the details of nearly 170 miles through 6 climate zones and an entire country? That required tapping into some previously unused gray matter and I’d done it so well I’d surprised myself. But the end of this journey? I knew it by heart. We’d top out at a restaurant with an overlook frequented by ATV tours out of Jaco. A final bump of a hill would indicate our highest point in the jungle and our reward? A 6 mile downhill rip to the outskirts of Jaco. Hold on!

Everything came and went with total recall. The wrinkle, because there is always a wrinkle, was that we were still under the forest canopy and the day had run out of extra light. Deftly dodging dips in the road gave way to simply holding on and sending it. I kept looking back, checking on Rick, and he was right there, stuck to my wheel. We benefitted from the headlights of a few cars following from behind. As the descent flattened out the canopy thinned, and we could see again. I check on Rick. Still stuck to my wheel! I pushed our pace. I held over 20 mph pursuing the finish line. With less than 100 meters to go we passed another racer! I looked over my shoulder and Rick was absolutely crushing his pedals!

A surreal ending. The dust kicked up from the motos, cars, and racers exiting the forest hung in the humid air and the sun’s final orange glow created a battle zone like environment. We’d been in battle. It felt appropriate. That embrace felt something greater than earned or mutual or powerful. Only Rick and I can understand what two men did on their MTBs while crossing Costa Rica together. Every coffee meeting, video call, training camp. Every lesson learned, hurdle cleared, and struggle shared. Each of his stories and my votes of confidence. The whole thing boiled down to those few seconds in the fading light of December 2nd, 2023.

A newbie took on an incredibly challenging sport with his sights set on the finish line of said sport’s hardest challenge. And he succeeded. And yeah… he’s 68.

Daily Highlight Videos

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Comments